If you’re doing as much as you can to live a greener life and you’re not acquainted with Nancy Birtwhistle, that’s something you need to remedy ASAP.

And if you’re thinking that you don’t have the means to follow fancy sustainable lifestyle tips, then that’s yet another reason to follow Nancy B. The best-selling author and influencer doesn’t push any products; on the contrary she shows you how to save money by cutting back on stuff, chemicals and energy costs by making or doing it yourself – and yes, that extends to making her own compost pile.

Because Nancy never recommends products, followers have overwhelmed her with questions about where to get some of the basic items she uses, especially for home-made cleaning creams and sprays. To help out, she invited followers to nominate their favourite eco-suppliers and a list of these is pinned to the top of her Instagram account.

We’ve been following Nancy’s advice for nearly two years, long before she had the world-wide 594,000 followers she has today. We make up her cleaning spray recipes instead of buying ones that are damaging to the environment and we’re glad to see she now appears regularly on BBC’s Morning Live.

I introduced my Greek daughter-in-law to Nancy and she’s a fan now too. Having grown up during Greece’s financial crisis, my daughter-in-law remembers her family making a little go a long way. This included growing their own food and making their own olive oil. She’s also passionate about recycling, having seen at first hand the devastation that climate change is wreaking on her country with increasing forest fires, heatwaves and floods.

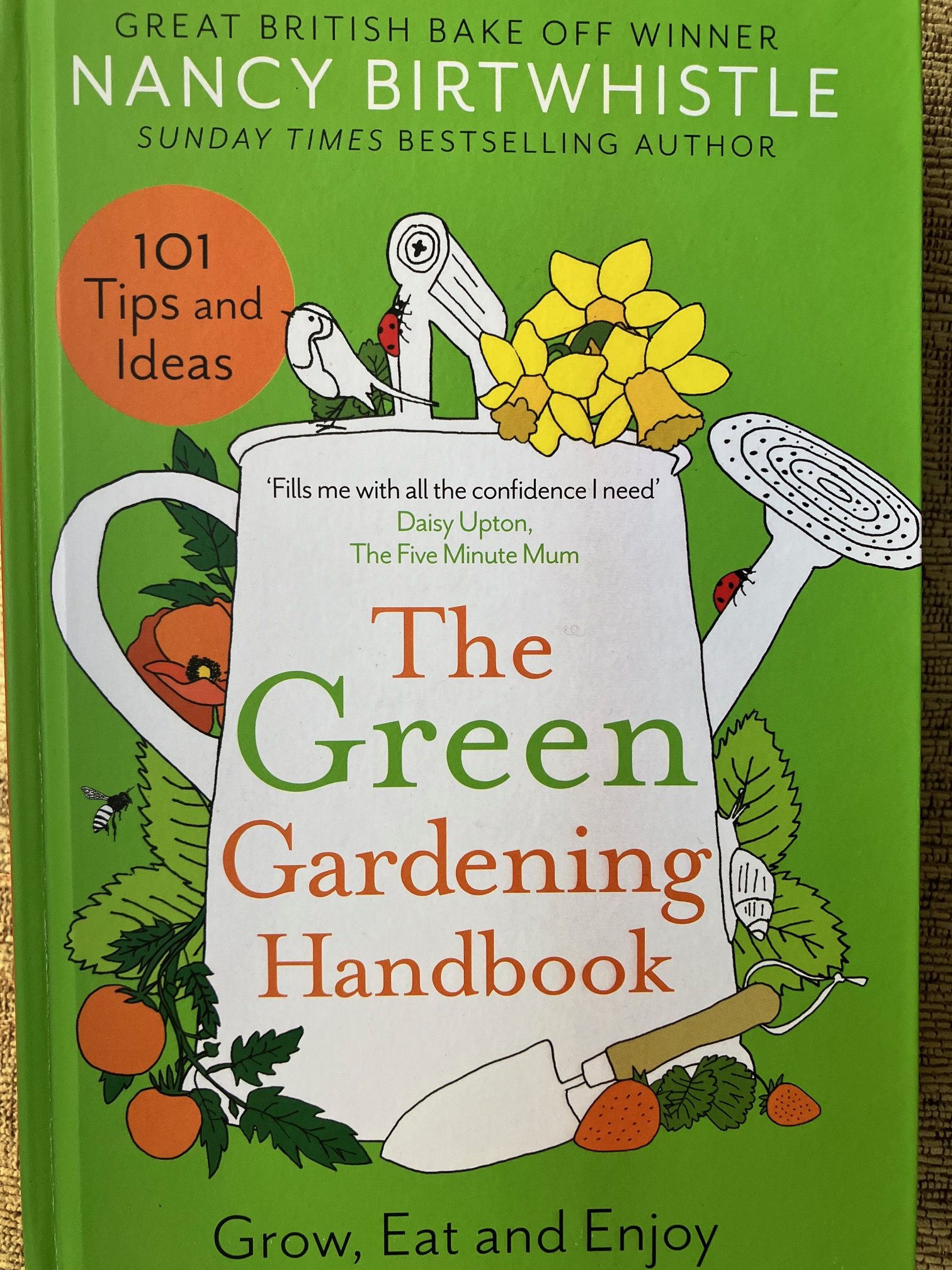

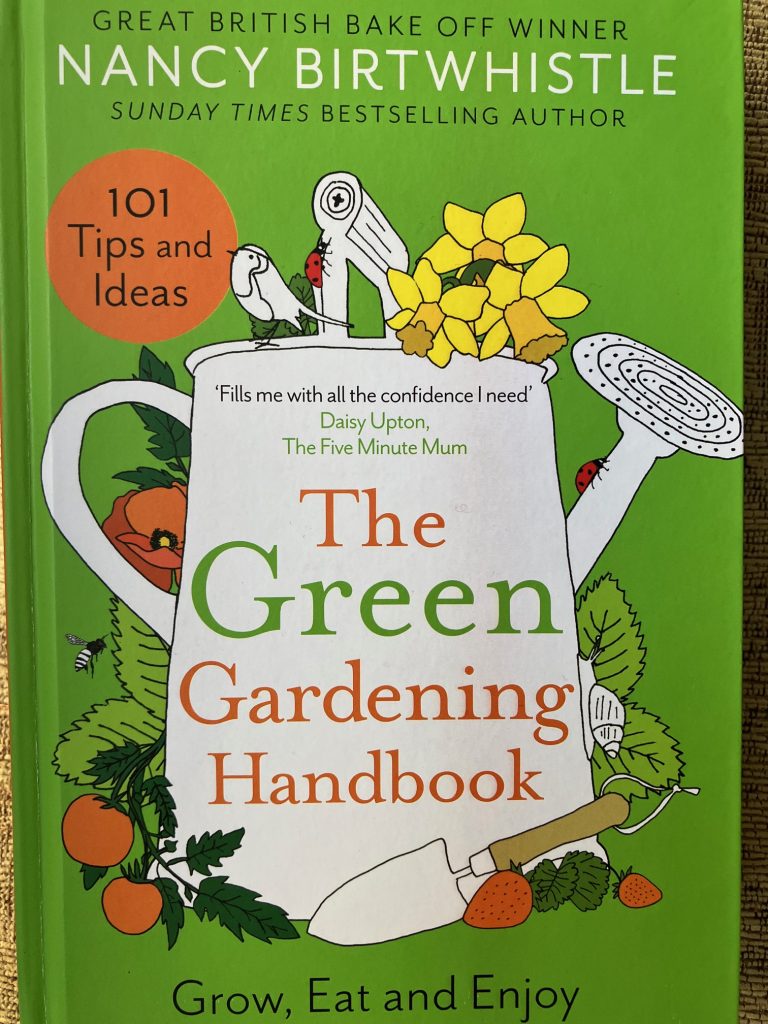

Back to Nancy – her latest book, The Green Budget Guide, was published last month and it’s my new bedtime reading. I’m gripped; it’s not so much a Whodunnit as a Howdunnit.

For example, for a long time I’ve wanted to learn how to darn socks but just never got round to finding out. This is something I remember my grandma doing when I was a child if she spotted my big toe poking out through a sock. The sock would be whisked away and returned with beautiful, neat darning that lasted forever. How incredibly wasteful to throw a pair of socks away just for one hole. Well now I know what to do, thanks to a snippet in Nancy’s book.

Advice is included on how to rescue items instead of throwing them away, make flexi-recipes, create your own gifts, freeze fruit and veg so it doesn’t clump into a solid block, make odour neutraliser for second-hand clothes and furniture, use up expired spices and ‘mop up’ shards of broken glass using slices of bread.… the list is endless.

As food waste is a subject close to this blog’s heart, we thought we’d share a section from the book on this topic.

Do you know what is the single most wasted food in the UK?

Bread. Around 20 million slices a day get binned.

Let’s change this. If you have a small household, it’s a good idea when you buy a loaf, to put half in the freezer. The second half can be thawed in less than an hour. If you live alone, freeze the whole loaf and take slices as required. Frozen slices of bread can easily be separated from the loaf using the blade of a round-ended knife.

The plastic wrapping that contains shop-bought loaves encourages mould because the bread’s moisture as it evaporates has nowhere to go. Nancy remembers that when she was a child, bread was sold in waxed paper. She has come up with her own method of making reusable, washable, long-lasting cotton bags that are coated in beeswax. These remain breathable and thanks to the anti-bacterial qualities of beeswax also resist mould. Her recipe uses thin cotton fabric, greaseproof paper, pellets of beeswax and an iron to melt the wax.

Because processed white sliced bread in plastic wrapping turns mouldy before it goes stale, keep an eye on it and get to it before mould appears so you can upcycle it with the following tips:

- Freeze breadcrumbs – Cut into 2.5cm chunks then blitz in the bowl of a food processor using the blade attachment. The breadcrumbs in this state will freeze perfectly so simply place in a bag or box and use them from frozen. Home-made bread tends to go stale and hard before it goes mouldy and can be grated if you don’t have a food processor.

- Instant thickener – Adding dry flour or cornflour to a hot casserole or sauce will create lumps so always mix the flour to a paste with a little cold water first before stirring through. Alternatively use breadcrumbs as a last-minute speedy thickener. Stir in a tablespoon at a time to quickly thicken without fear of lumps.

- Instant crunch – heat 1-2 tablespoons of oil in a frying pan then sprinkle over a cup of fresh breadcrumbs, a sprinkle of dried garlic and dried herbs and fry until crisp and golden. This makes a tasty instant crunch to top off a shepherd’s pie, fish pie, pasta bake or salad.

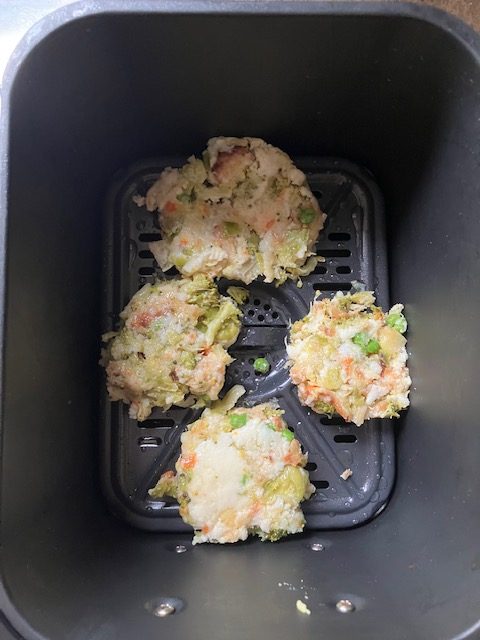

- Shelf breadcrumbs – If you’re stuck for freezer space you can dry your breadcrumbs: spread the fresh breadcrumbs on a baking tray in a thin layer and place in the oven to dry out. If the oven has been on for something else, pop in the tray of breadcrumbs when you have finished cooking and before the oven cools down. The breadcrumbs once dried, will feel coarse and will not stick to the hands. For a very fine crumb, blitz again in a blender once dried. Once cool, the breadcrumbs can be stored in a jar in a cupboard indefinitely – perfect for coating Scotch eggs, fish cakes, fish fingers, chicken and vegetables.

Check out Nancy’s account and books – you’ll make small changes to the way you live, and those changes will make a big difference.

Julie