Some years ago my toddler son was out jumping in puddles in his little red wellies, when I noticed some worms. I pointed them out to him and was completely horrified by what he did next – he raised a booted foot in order to smack it down on a worm.

I don’t know why he was so freaked out. Had he never noticed them before? Were they so different to cute animals – without faces or fur – that he found them scary? Obviously I stopped him and told him how wonderful they were.

Children are fascinated by worms but it’s not always a given that they love them. One of our young worm farmer friends, aged 8, said some children in his school were mean to worms when they encountered them.

Worms could do with an image makeover that sees them recognised as eco-superheroes – and now is the time with tomorrow (October 21) being World Earthworm Day.

It’s wonderful that these under-appreciated creatures get their own day, although those of us who compost think every day is earthworm day.

The day commemorates the publication in October 1881 of Charles Darwin’s book The Formation of Vegetable Mould Through the Actions of Worms, which changed how worms were viewed.

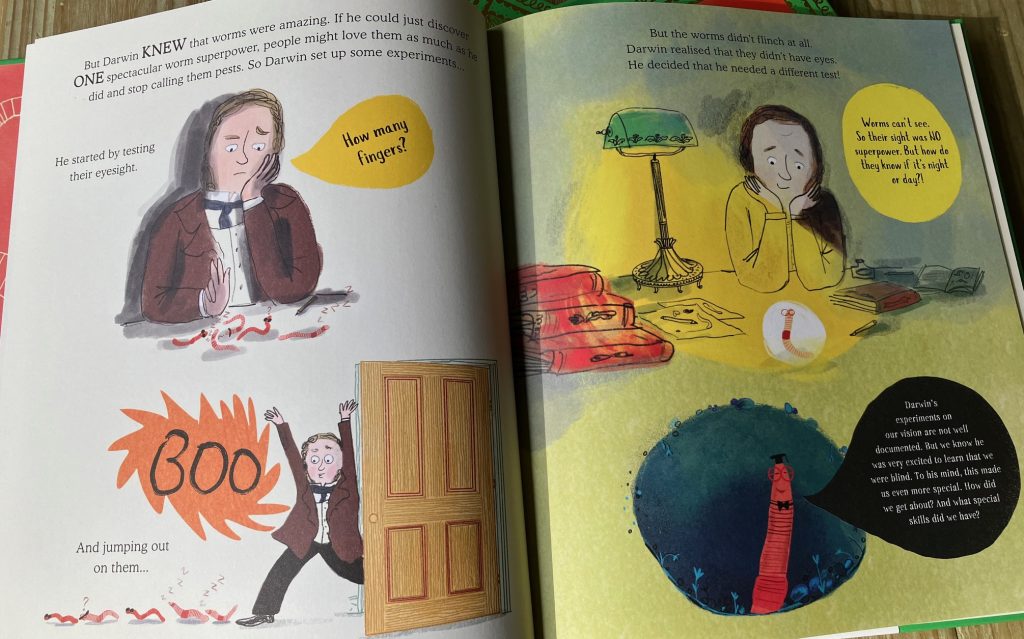

Of all the creatures that Darwin studied, earthworms were the ones that interested him the most; he spent 40 years studying them. His studies and experiments attracted the mockery of other scientists because worms were considered pests at the time, but Darwin was convinced there was something special about them. He tested their eyesight and hearing, concluding that they were blind and deaf but could detect vibrations.

Feeding worms showed him they liked celery, cherries and carrots but not sage, mint and thyme. He found that they also eat stones to grind up leaves in their stomachs as they have no teeth.

It became something of an obsession with him. At times he doubted himself and wondered if he was being foolish. People who admired Darwin for his previous work couldn’t believe that he was devoting so much time to such an ‘insignificant’ creature. But Darwin believed that the apparently insignificant can be the foundation of something much greater. As we know, his dedication paid off.

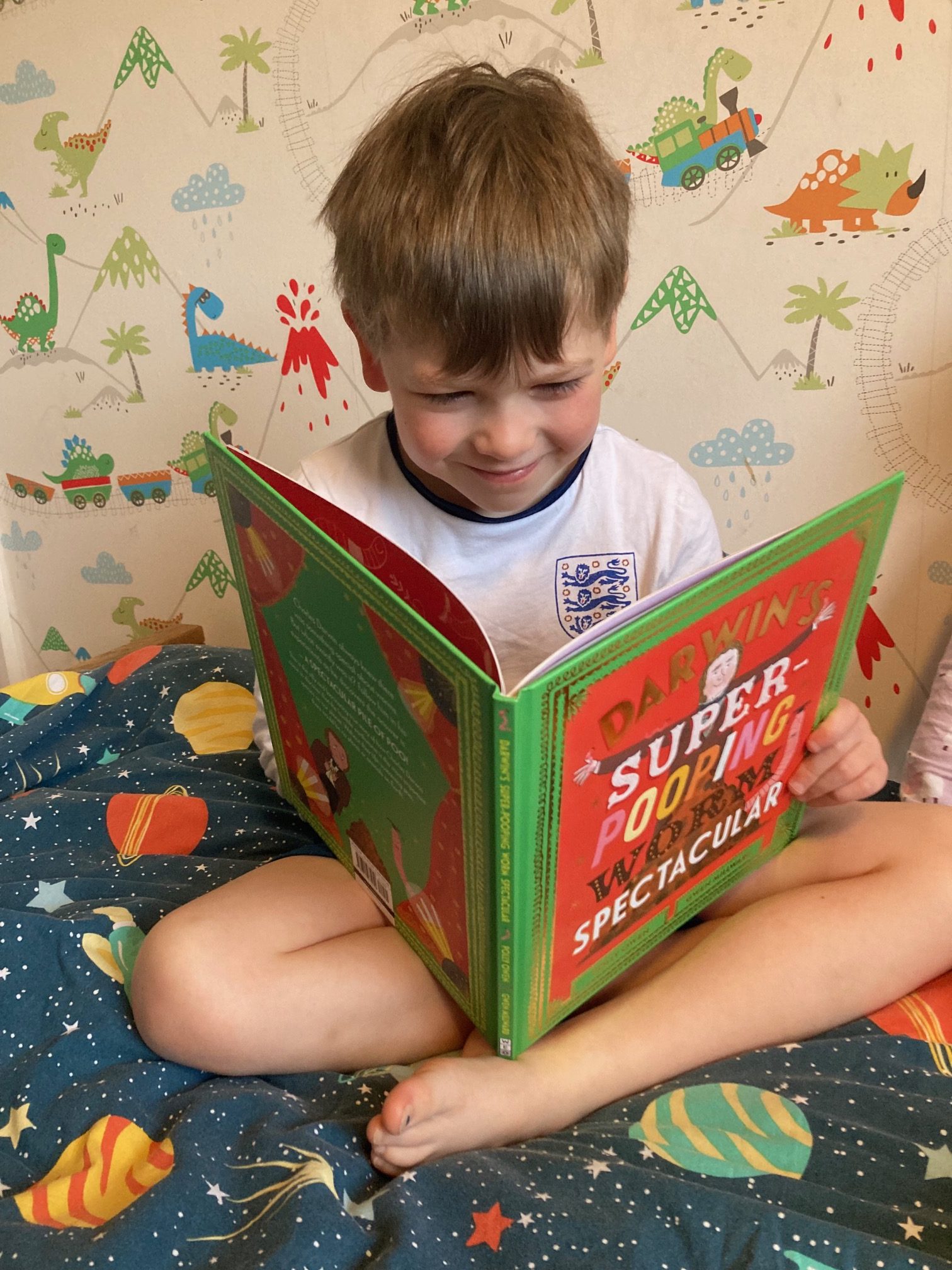

An illustrated children’s book on this subject was published earlier this year – Darwin’s Super-Pooping Worm Spectacular by Polly Owen. It tells the fascinating story of how Darwin came to conclude that the humble earthworm was the most important species on the planet. For a long time he didn’t find evidence to back up his belief that worms were special, until one day when he discovered their superpower, one that sustains life on earth. We won’t spoil the story!

The Great Green Systems team loves this book and so too do our young worm farming friends, Reggie and Magdalena, shown here reading it.

Reviews by parents and grandparents who have read it with their children and grandchildren show that adults can learn from it too. Several reviewers say every classroom should have a copy as it’s an ideal subject for primary school science.

As well as introducing children to Darwin and the ways that scientists make deductions, it’s also an inspiring story about the triumph of a person who ignored mockery to persevere with something he believed in.

BBC Wildlife called the book ‘a disarmingly silly read that manages to share cool worm science with a light and easy touch.’

From saint to sinner and back again – worms’ changing reputation

Past

The fact that worms are vital to soil health – and therefore to us – was well known to the ancient Greeks and Egyptians. Cleopatra decreed that the earthworm should be protected as a sacred animal as it was believed that harming worms or removing them from the land would affect the fertility of the soil. But this wisdom somehow got lost and by Darwin’s time worms had fallen out of favour and were thought to be pests that killed plants, damaged the soil and made a mess of gardens.

Present

We know that worms aerate and improve the soil, providing nutrients for plants to flourish. Without them the earth would become cold, hard and sterile.

The few centimetres of soil beneath our feet have typically been the least studied place on earth but today scientists all over the world are following Darwin’s example. The simple act of introducing worms to degraded soil in poor regions of the world has been shown to increase plant yields by 280%.

Gardeners know that vermicompost (compost produced by worms) is ‘black gold’ – the best quality soil food.

Future

Despite our knowledge about how dependent we are on earthworms, the species is in danger from humans. Chemicals sprayed on plants by gardeners and farmers cause them harm and artificial grass is also a danger as they become trapped below it.

But there’s a lot we can do to help them. In our gardens, parks and allotments we can compost and create log piles. We can also use ecological gardening methods which don’t rely on chemicals.

To learn more about worms and how to help them, join The Earthworm Society – www.earthwormsoc.org.uk.

Let’s spread the word about worms at home and in schools so that never again will a child try to stamp on one or be mean to one. Like my son, Magdalena used to be scared of worms when her family first got a worm farm but several months later here she is confidently checking they’ve got enough to eat.

It’s appropriate that Darwin should get the last word.

After his long years of study, he concluded: ‘It may be doubted whether there are many other animals which have played so important a part in the history of the world as have these lowly, organised creatures.’

Julie